Enough For Everyone

1 Thessalonians 2:9-13

You remember our labour and toil, brothers and sisters; we worked night and day, so that we might not burden any of you while we proclaimed to you the gospel of God. You are witnesses, and God also, how pure, upright, and blameless our conduct was towards you believers. As you know, we dealt with each one of you like a father with his children, urging and encouraging you and pleading that you should lead a life worthy of God, who calls you into his own kingdom and glory.

We also constantly give thanks to God for this, that when you received the word of God that you heard from us, you accepted it not as a human word but as what it really is, God’s word, which is also at work in you believers.

The folks who put the chose what readings go when in the lectionary made some strange decisions. Because today’s passage shouldn’t have been separated from last week’s. It would have made much more sense for 1 Thessalonians chapter 2:1-13 to have been just one scripture lesson. With that being said, there are two things we’ll have to remember from last week’s lesson for this week’s to make sense.

The first one is that we have to remember the imagery of infant and the nursing mother. Paul writes, “…we were gentle among you, like a nurse tenderly caring for her own children.” And ‘gentle among you’ is probably better translated “we were like infants among you.”

The second part to keep in mind is one that we didn’t really touch on last week. Right before the imagery of the nursing mother, Paul writes that he and the other apostles “…did not seek praise from mortals…though we might have made demands as apostles of Christ.” Paul is saying here that technically, they have the right to make demands of people because of authority given to them by Jesus, but they wouldn’t dare do such a thing—and that is what leads into them coming to Thessalonica like infants, and like unconditionally loving and sustaining nursing mothers. They don’t intent to force anyone into anything. That would defeat the whole purpose.

So now onto this week— Paul goes from infant, to mother, and now, “…like a faither with his children…”. So now we have the whole family— two parents, both providing unconditional love, sustenance, and guidance, but at the same time, making it clear that, despite being apostles of Christ, they’re on equal footing with their new friends who are just beginning this new journey. They’re all in their infancy together, exploring and discovering, and figuring out what works.

There are probably a number of reasons Paul chooses these metaphors of a family unit to convey his message of love. And one of those reasons is likely because, sadly, many of these new Jesus-followers may have been disowned or shunned from the family for their new beliefs. I’ve talked about the concept of “chosen family” in sermons before—these days, chosen families are often talked about in the context of queer community—LGBTQ folks who have been abandoned by their families of origin for no other reason than who they love. But chosen families exist in every context—for people who come from abusive, or negligent households; for people whose values are at odds with their family of origin. And chosen family doesn’t have to come from trauma or abuse—we can find different kinds of love and fulfilment thanks to our non-blood-related loved ones, we can be ourselves in different ways, we can come together to work for something we all believe in. We find chosen family by finding people who want to work for the same earth as it is in heaven that we want to work for.

And I think, when it comes to chosen family, there’s not that built-in authority that we inevitable have with our parents, right? Or at least there shouldn’t be. That’s why this strange contradiction of Paul calling himself infant, mother, father, all in one works so well—while the apostles can, and indeed do, guide and love, they are also not above their friends. There are no hierarchies on the earth as it is in heaven they are working for, and therefore, there should be no hierarchies within this new faith community, within this new faith family. That is the beautiful thing about a faith community, about the communities we choose, right? We’re working together, as one. We don’t look to one person and one person only, we look to one another. We all have this ultimate authority in Christ, Creator, and Spirit, and that is ultimately an authority of Love—that is the ultimate unconditional parental Love that we are all trying to emulate here on this broken world.

So this chosen family, this chosen church family, is where we come, for a brief time, to escape the oppression of the outside world. It’s where we come to get just a taste, a preview of the peace and the freedom of life together, a life with no false authorities, no judgment. At the end of the passage, Paul says that his new friends have “…accepted [the word of God] not as a human word but as what it really is…which is also at work in you believers.” This is where we come to really try to commune. This is where we come to figure out what really and truly matters. And we don’t come here because we’re forced to, or out of obligation. We come here because we want to. We want to experience the possibilities that Jesus preached about, and we want to work to make them a reality.

And that truly wanting to, that’s the next thing we have to remember from last week. Paul and his apostles could have come into Thessalonica and made demands of these folks. They could’ve used their authority given to them by Jesus, but they didn’t. First of all, I don’t think this is ever a good tactic. Forced conversion is an awful thing, and even if Paul and his co-workers could have forced people into following Jesus, that makes being a Jesus-follower moot. Because being a follower of Jesus means truly wanting to change the world for the better. It means working side-by-side, in community with others to repair the brokenness. When Paul says that like a faither he is “urging, and encouraging…and pleading…” that can sound a little intense, maybe a little desperate to our modern ears, but the truth is, that’s the opposite of demanding. Paul is really just telling the Thessalonians what is possible when you do the work Jesus calls us to do. He’s encouraging them, telling them the good news that a just world, a world where there are no hierarchies, a world where we can all live as one loving family is possible. And when they come to this realization on their own, which they do, that is one huge step towards a just and equitable world.

Today is a Communion Sunday, and so it’s perfect that this next part of the sermon is all about being invited. Because that’s what this urging and encouraging really is—again, it’s the opposite of demanding. So Paul is enthusiastically inviting people to the table with Christ—because, as we know all are invited to the table—regardless of gender or sexual identity, regardless of race, regardless of socioeconomic status—all we unconditionally and enthusiastically welcome here.

In his book Community: The Structure of Belonging, author Peter Block writes of the concept of invitation:

It manifests the willingness to live in a collaborative way. This means that a future can be created without having to force or sell it or barter for it. When we believe that barter or subtle coercion is necessary, we are operating out of a context of scarcity and self-interest…

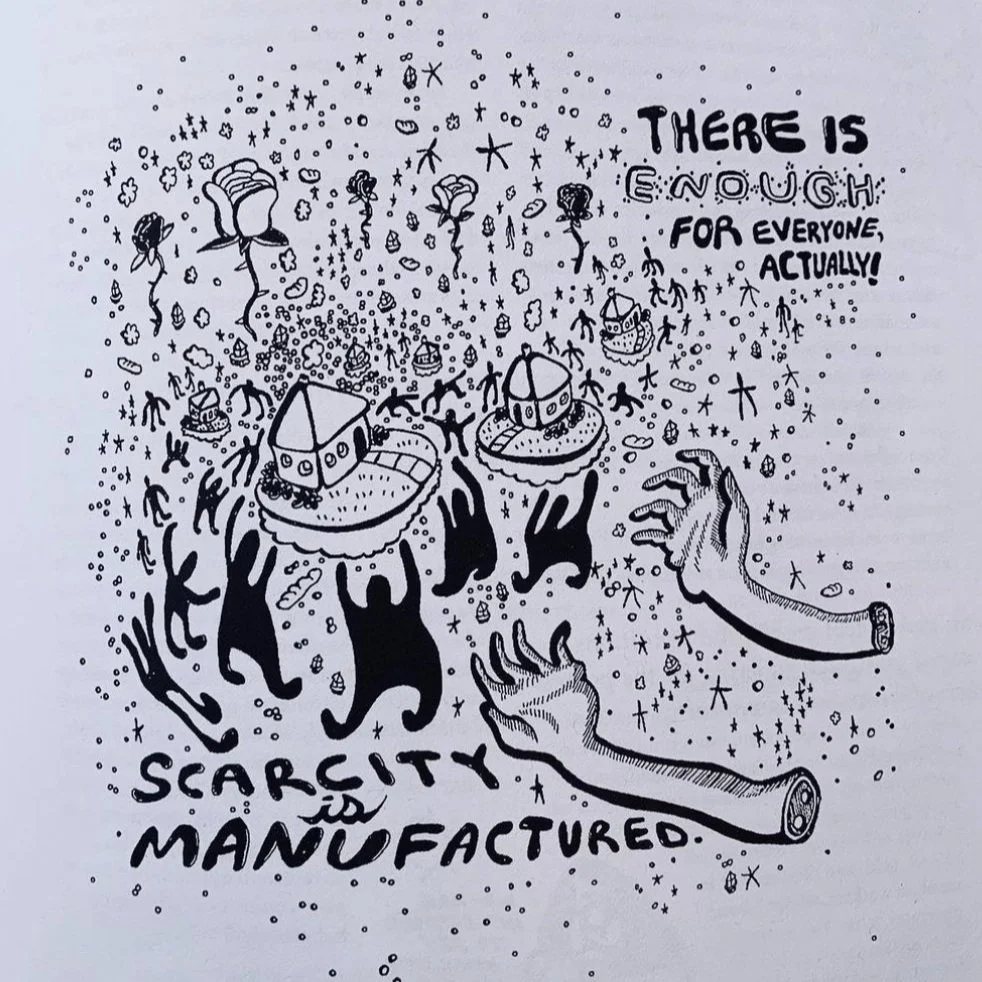

There’s a postcard I have hanging on the bulletin board outside my office that reads “Scarcity is manufactured. There is enough for everyone.” The economic and cultural systems we live under manufacture scarcity to keep the vast majority of us down. And scarcity and self-interest go hand-in-hand, because if we don’t think there’s enough to go around, then we have to fight for ourselves and for our loved ones. It’s a survival of the fittest kind of mentality. And I think that’s the problem with so much of mainstream Christianity today— there are big promises being made—that your life is gonna change, that you’ll be at peace, that this perfect paradise awaits you in the afterlife, and all you have to do is be baptized and give us money. It really individualizes a faith tradition that was always a communal one. It makes it all about one’s own self-interest and future, and not that of all people.

When people come to this church, none of us can promise them that their life is going to change exponentially. None of us can promise that if they come here and pray, they’ll get that perfect job, they’ll meet the love of their life, and when it’s all over, they’ll be in some perfect city in the clouds with roads paved with gold. But we can promise unconditional love and support. We can promise to not judge the people who walk through these doors, who comes to experience fellowship in the Holy Spirit. We can promise to treat them as family.

Now this concept of invitation is harder to put into action than it seems, especially when it comes to inviting people to church in the northeast. A simple invitation can be looked at as some kind of coercive evangelizing, and so it’s hard to get up the courage to do. But in that same book on community, Peter Block articulates the feeling about the rejection of an invitation in a really perfect way I’d never been able to put into words. He says, “I do not want to have to face the prospect that I or a few of us may be alone in the future we want to pursue.” He goes onto say, “My fear is that what I long for is not possible, that what I invite them to is not realistic, that the world I see cannot exist.” Oof. I wish that didn’t speak to me so strongly. I wish I didn’t have this cynical fear in my head that people don’t want change, that people don’t want true equity, that people don’t want a just world where all are safe and at peace. And that’s lonely, right? That is a lonely, lonely fear.

It's ironic, I think, that the thing that keeps us apart, the thing that keeps us from inviting people in is the fear that we will continue to be the alone. It’s a vicious cycle that, it’s the snake eating its own tail. But when we look at the world these days, it’s easy to think that you’re the only one who cares. It certainly doesn’t seem like anyone in power, anyone the media focuses on cares. And I think that’s why it’s easy to feel so alone in this world, why it’s easy to think that if we invite people in they won’t be interested. The media we watch, the news we see, certainly makes it seem like the vast majority of people prefer violence and death over peace and freedom. And this also goes along with the manufacturing of scarcity, doesn’t it? It makes it seem like the people who believe what we believe are few and far between, and so what’s the point?

But we know none of that is true. We know that the majority of people do want a place where everyone is safe and loved. We see a glimpse of that here, every Sunday, knowing that this is a place where everyone is truly safe and loved. This is a place where we can, for just an hour or so, escape the judgment and manufactured scarcity of the world and feel the abundance of Love that’s promised; the abundance of love that is always available to everyone. It’s just hard to feel sometimes outside these doors.

So I want us to go from today figuring out how we can invite people in, figuring out how we can let go of that fear that people just don’t care, that we’re the only ones. Because that’s ultimately a selfish way of thinking, and that’s how the powers that be would want you to remain—selfish and isolated—so that they can continue to hoard their wealth and fight their wars. But if we invite people in—both literally into our homes and into this church, and figuratively, into our hearts and minds—we will grow and we will see that it is possible to band together as one family, full of unconditional support and love. God’s word is so clearly at work in each one of us. So let’s allow that work to invite people in. Amen.