Ever More Different

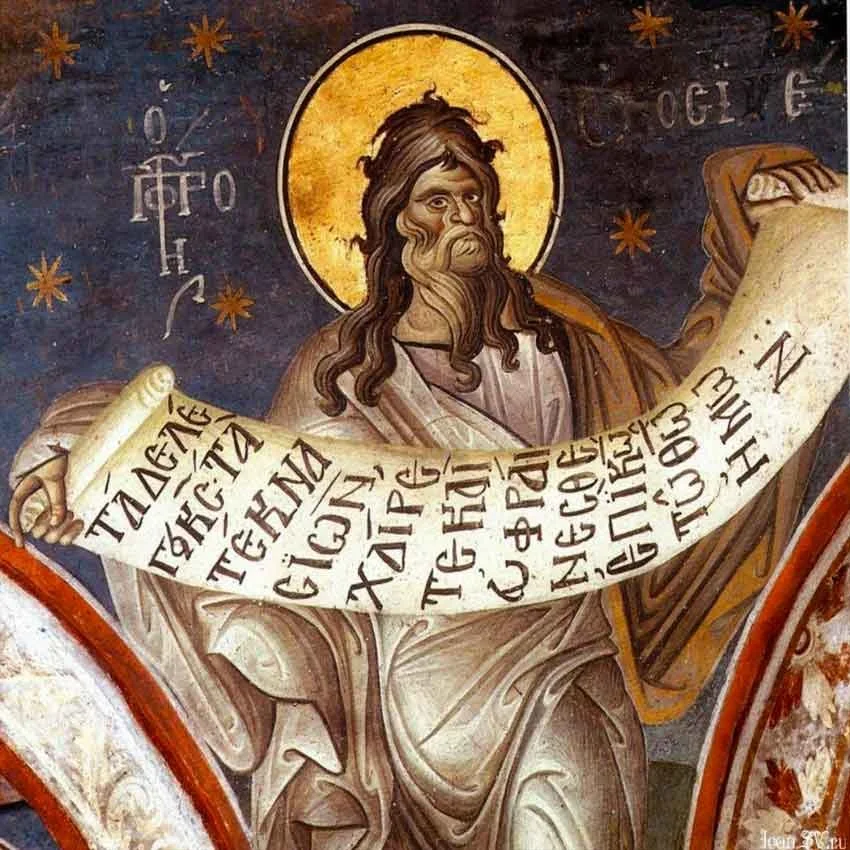

Joel 2:23-32

O children of Zion, be glad

and rejoice in the Lord your God;

for he has given the early rain for your vindication,

he has poured down for you abundant rain,

the early and the later rain, as before.

The threshing-floors shall be full of grain,

the vats shall overflow with wine and oil.

I will repay you for the years

that the swarming locust has eaten,

the hopper, the destroyer, and the cutter,

my great army, which I sent against you.

You shall eat in plenty and be satisfied,

and praise the name of the Lord your God,

who has dealt wondrously with you. And my people shall never again be put to shame.

You shall know that I am in the midst of Israel,

and that I, the Lord, am your God and there is no other.

And my people shall never again

be put to shame.

Then afterwards

I will pour out my spirit on all flesh;

your sons and your daughters shall prophesy,

your old men shall dream dreams,

and your young men shall see visions.

Even on the male and female slaves,

in those days, I will pour out my spirit.I will show portents in the heavens and on the earth, blood and fire and columns of smoke. The sun shall be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood, before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. Then everyone who calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved; for in Mount Zion and in Jerusalem there shall be those who escape, as the Lord has said, and among the survivors shall be those whom the Lord calls.

I struggle with this one. Not only does it have some of the examples of the infamous angry God, it also just reads as much more… archaic than other parts of the Bible, new or old testament. It struck me as similar to ancient myths—especially the mentions of locusts as God’s army, reigning destruction the crops—it all feels very reminiscent of ancient myths using God’s anger, or fate or destiny, as we talked about last week, as rationale as to why bad things are happening, why the crops are failing, why the locusts are destroying.

Now, Joel is considered a minor prophet for a reason—his book is short, and very little is known about him. It’s even unclear when he lived; the only thing we can confidently assume about him, is that he wrote during a time of famine due to a plague of locusts. So, desperate for some extra context, for something to help me along here, I went way back to some of my undergraduate texts on myth. Because as uncomfortable as it can be to refer to the Bible as myth, while it might create a sort of contradiction for us—how can the word of a God we believe in also be considered mythology, the fact is, that these stories were passed down through oral tradition, that educated people in power transcribed and compiled these texts and there are a lot of missing pieces and context, there’s a lot we just can’t know, and there’s a lot to wrestle with.

Just for practicality’s sake (read: laziness), I found the skinniest book of myth I own, the famed anthropologist and philosopher Claude Levi-Strauss’ Myth and Meaning. It just so happened that I found something in this tiny book that made something click for me.

Now, Levi-Strauss is dense. He is not easy to understand, so I’m going to do my best to explain one of his core beliefs—he ultimately believed that the disciplines of science and history were slowly taking over myth and religion—but he also knew that for every answer, every advancement, there will be ever more questions and new unknowns (as we kind of touched on last week), and so there will always be a reason that myth will still exist, and that religion, philosophy, etc., must continue to exist in some capacity. History was slowly taking over for myth, but it is still so intimately intertwined with myth, due to the fact that so much of our most ancient history comes from the most unbelievable and fantastical stories—from oral tradition, histories told around a fire. In his chapter “When Myth Becomes History,” he writes, “…for societies without writing and without archives the aim of mythology is to ensure that as closely as possible…the future will remain faithful to the present and to the past. For us, however, the future should be always different, and ever more different, from the present…”. This is what hooked me, this is what made the lightbulb go off.

Because in these ancient days, people were trying to remember stories, remember histories, so that they would stay true to their roots, so they wouldn’t betray their beliefs or their faith. They wanted to be faithful to the past and to their ancestors. And this is all well and good to an extent. But when we are able to look back towards the past thanks to the written word, we can do more than just repeat stories in order to keep the status-quo. We can learn from the past, and we can change for the better. We can learn from the past and stop continuing the make the same mistakes over and over. So Joel was relaying this strange poem at a time when they were rationalizing these very real and traumatic events with memorable and fear-based beliefs in a God that was so angry with them. But remember last week—God revised the covenant. And remember that this new covenant would no longer involve borders or walls—God’s love would now be written on the hearts of all people, no longer confined to a certain place.

I will pour out my spirit on all flesh;

your sons and your daughters shall prophesy,

your old men shall dream dreams,

and your young men shall see visions.

Even on the male and female slaves,

in those days, I will pour out my spirit.

This, to me church, seems like a part of God’s new covenant—a time when prophesy is no longer only given to certain people, a time when all are on equal footing, a time when slaves are no longer slaves if they’re seeing the same dreams and visions as everyone else. So this passage is a strange and perplexing mix of the old—of this angry God raining destruction on their own people—and the new—of a time when all shall eat in plenty, when no one will ever again be put to shame.

I wonder if this was a strange in-between time, a time when people were still trying to hold on to the ideals of old while looking forward to a new, more perfect world, where this fear and shame-based culture would no longer exist. I wonder if there was still a strange pull to the old, the outdated, and the familiar, with also a push to the new, the exciting and groundbreaking. That’s what I’m seeing in today’s scripture. I’m seeing a people who are dying to break away from the constant ups and downs, of the seemingly constant crises; but I’m also seeing a peoples holding onto the past. I’m seeing a people still trying to rationalize why these events are happening instead of looking for a true way out. They see the endpoint, but they don’t know quite how to get there yet. The book of Joel has a very nationalistic bent to it, which, remember, is kind of counter to God’s new covenant, God’s Love that cannot be contained, the Love that cannot be reduced to being of only a certain place and time.

This feels very familiar to me. We don’t seem to want to learn from our mistakes, just like the Judeans of Joel’s time— these days we’re battling inflation created by corporate greed, we have the powerful raising interest rates instead of moving to find something new, something that actually works—they’re continuing to use the same tactics that just don’t work for this new world. We’re battling pandemics and various other health crises—addiction, mental illness, especially within younger generations, and yet the healthcare system remains the same—unattainable and unnavigable to so many. We know we need to do things better. We know things need to change, but for some reason, we just don’t seem to be able to make that next step, we don’t seem to be able to understand that a better world is possible with a new outlook. We don’t seem to understand that remaining tied to the old ways is doing so much more harm than good.

And you know, the same goes for the church. I think it’s been clear for some time, even pre-covid, that things need to change, the church can’t keep doing things the same way. And now we seem to be in this strange limbo, where the pandemic made it crystal clear things can’t go back to the way they were, but it did it before we were ready. Change is hard enough without being rushed into it, right? Even when something’s not working, we want to stick with what we know. It’s comfortable, it’s easy. There’s this great book Devil House by John Darnielle, and in that book there’s an incredible quote about nostalgia: “The past is charming and safe when you’re skittering around on its surface. It’s a nice place to linger a moment before seeking the lower depths.”

It’s so interesting to me, the huge dichotomy you have between this angry vengeful God, both at the beginning and at the end, when apparently Joel is talking about Judah’s enemies being vanquished—and then you have this beautiful poetry about a world with no more shame, a world where everyone is fed, a world where the Holy Spirit is poured out and accessible to every living being, regardless of their status in life. It seems to be that we have to find the in-between. Not a compromise; rather, we have to find, quite literally, what comes in between this past of a fear and shame-based society, to this perfect earth as it is in heaven in which everyone has a direct connection with God, in which everyone is sated and happy. I’m especially thinking about the shame aspect in all of this—I just read the former child actor Jeanette McCurdy’s wonderful but brutal memoir, and in it, she talks about the feelings of shame she always had that absolutely took over her life. In talking about her process healing from her substance abuse issues and her eating disorders, she writes, “…if we beat ourselves up after a mistake, we add shame onto the guilt and frustration that we already feel about our mistake. That guilt and frustration can be helpful in moving us forward, but shame… shame keeps us stuck. It’s a paralyzing emotion. When we get caught in a shame spiral, we tend to make more of the same kinds of mistakes that caused us shame in the first place.” In thinking of this concept of a shame spiral, I find myself wondering if this was a vicious cycle the Judeans were stuck in—longing to move forward to that perfect world, but being held back by shame, by fear, in addition to nostalgia and a belief that because this is the way it’s always been, this is the way it should stay.

I think, as always, what comes between the past and the future is work. I think it’s creativity, I think it’s new ways of thinking. It’s too easy and it’s ultimately harmful to look back on the past with too much nostalgia, to wish we could go back in time to when things were “easier.” Because when we do this, as that quote says, we’re just looking at the charming aspects of the past, the nice memories we have of things before they got too complicated, too confusing. But if we dig, and we don’t have to dig that far, we can see that the past was far from perfect. If we dare go to the lower depths we will see all the reasons we need to continue moving forward that we cannot forget the past, but that we have to change our ways to survive, and that we have to change our ways to bring about an earth as it is in Heaven. The trick is, is to do this, to go to those lower depths without falling into that shame spiral leading us to just make the same mistakes over and over. Because to move forward, we need things to be ever more different than the previous era.

At our trustees meeting on Thursday, we discussed the inevitable topic of our famous roast beef suppers—what are we going to do? Do we bring them back? If so, how? What will they look like? Will we have the volunteers? Will we have patrons? Can we bring them back without falling into the trap of nostalgia? Well, we’ll discuss that at our quarterly meeting after church today. But even more than that, looking at the bigger picture, what I really want to know—is can we work on building on the radical hospitality we show with the roast beef suppers? Can we do more? Can we do things a little differently? Can we find new ways to be a true community gathering place, can we continue to be an anchor to this community, a place of safety, comfort, and hope in a world that is becoming more and more fractured, in a world where people are becoming more and more isolated? I think so. I really think we can, but it’s going to take work, it’s going to take a renewed sense of duty and devotion to the things that bring people of all walks of life together—a renewed sense of understanding, welcoming, and outreach.

I keep telling folks that we’re in a strange period of limbo, that we’ve been here for pretty much all of my time so far in this community. And realistically, we might be here for a little longer, and that’s okay, we just have to be a little patient—but we can’t move backward. We can’t fall prey to nostalgia or worse, to shame, and continue to do things the same ways we’ve always done them. As we look forward and learn and grow from our past, we’ll continue to do things ever more differently—and that’s how we’ll get out this limbo, and get to that perfect world where we will never again be put to shame; where we will eat in plenty and be satisfied; where God’s spirit will be poured out on all people. Amen.