In the Mud

Matthew 3:13-17

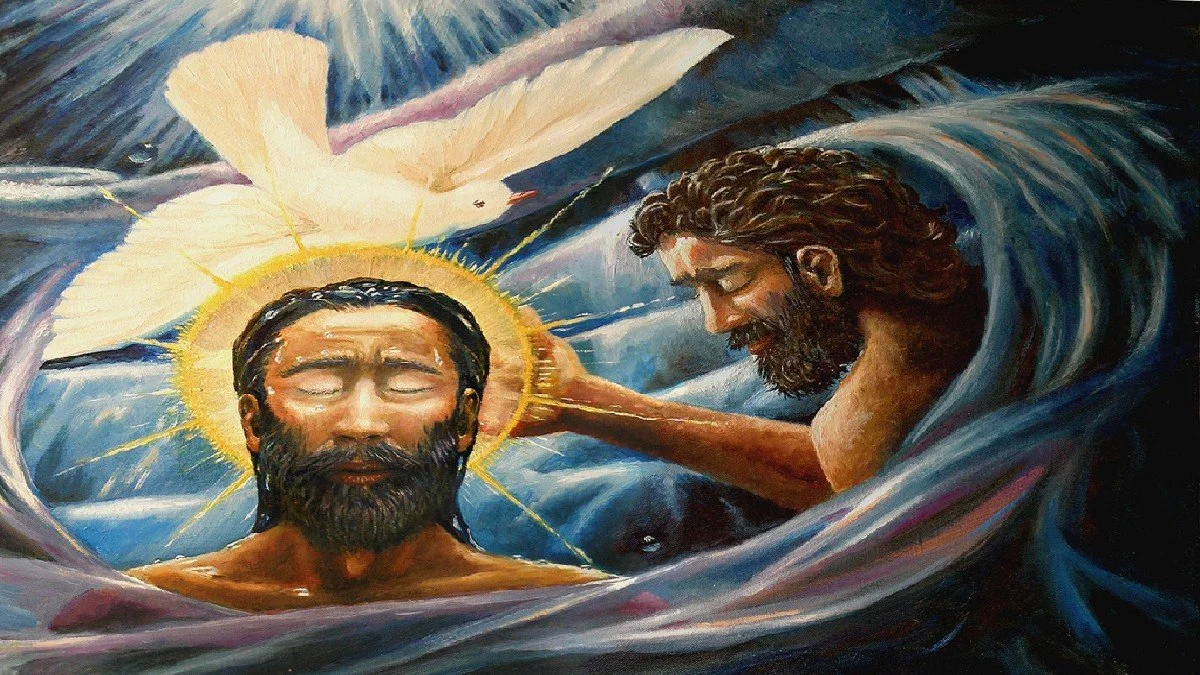

Then Jesus came from Galilee to John at the Jordan, to be baptized by him. John would have prevented him, saying, ‘I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?’ But Jesus answered him, ‘Let it be so now; for it is proper for us in this way to fulfil all righteousness.’ Then he consented. And when Jesus had been baptized, just as he came up from the water, suddenly the heavens were opened to him and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him. And a voice from heaven said, ‘This is my Son, the Beloved, with whom I am well pleased.’

This is one of those rare stories that’s in every single one of the four gospels. When it comes to stories like this one, it can be challenging to preach on— either one becomes overwhelmed with the many interpretations, differences and comparisons with each version of the story, or one can feel like—what more is there to say about a story so famous, so ubiquitous—the story of the baptism of Jesus? So when it comes to these ultra-famous scripture passages, I often try to find what is unique about the one we’re reading, and in Matthew’s case, it’s something pretty profound. It’s the only version in which this dialogue between Jesus and John takes place—the dialogue that Glenda just read for us—in which John is shocked by Jesus’ request to baptize him, and he makes it very clear that he believes it should be the other way around, that Jesus is above him, and therefore should be baptizing John.

There are several different ways to read this—one is the kind of boring, contextual, historical reading of it—that at this time in ancient history, there were many people who believed that John the Baptist, not Jesus, was actually the messiah, and that this was to make it clear to those people that that was absolute not the case; some theorize that there was probably backlash to the idea of Jesus getting baptized, critiquing the fact that there’s no way the true messiah who is holy and pure, free of sin would ever deign to be baptized, would ever need to be baptized—and there is surely some truth to these two interpretations, it just makes sense that a budding religious movement would have to defend itself in some way. But the reading that I love is one of solidarity. No, Jesus doesn’t need to be baptized. He chooses to be because he is one of us. He refuses to be “above” us. We are so incredibly blessed to have a savior who truly walks alongside us, who experiences everything we experience, who feels everything from our deepest sorrows to our most radical joys.

Some of you might remember my Christmas Eve message from a couple weeks ago— I talked about the evolution of the beloved Christmas carol Hark! The Herald Angels Sing, and how the version that we know and love today focuses not on the all-powerful God as Charles Wesley’s original lyrics did, but rather on “the new-born king.” I spoke about how this was maybe not Biblically accurate, but it is indeed theologically accurate—because in this new year, as we once again, in church, begin to discern the life and death and resurrection of Jesus, and outside of church, as we wonder what new ways we can be the church in the world, we are thinking of new ways to see things, new ways to simply be—in this new time, bringing glory to a vulnerable baby in a manger was the new and radical and right thing to do. I want to use a quote I’ve used in a previous sermon, from the book Pure Color by Sheila Heti:

“…when God blinds your eyes to [these things]…he opens your eyes to everything else. But what else is there? Seasons, birds, the wind in the trees. So don’t go chasing your old forms of sight. Instead, learn to see newly. Right now it may feel like a loss of sight, or like you don’t understand the things you do see, but there is still a lot to see here.”

This quote is perfect, not just for inspiration to see things differently in this new year, but also for this passage—because this passage is one beautiful contradiction, as all of Jesus’ life was. You have this kind of defensive stance that Matthew takes in order to make clear that Jesus is indeed the messiah, but then you have him, as our next hymn will read, wading “through murky streams,” literally getting down in the dirt and mud, with the rest of us—and then, as another stark contrast, we have this miraculous opening of the heavens and the Holy Spirit descending like a dove, and the literal voice of God! There is so much to see here.

I love the ambiguity of “like a dove.” The dove, this universal symbol of peace, and the Biblical symbol of hope, appearing after the great flood subsided. But I think the use of “like” gives us some wiggle room for how we see the Holy Spirit in the world. It lets us think of all the different ways we can experience the Holy Spirit. And if our savior Jesus can be born in a hay-filled manger, if our savior Jesus can be baptized just as we all have been, if our savoir can indeed be both human and divine, doesn’t that mean we should be able to experience the Holy Spirit in new ways? Maybe in mundane, every day ways?

I read two very different books recently, one I’m still reading, in which different characters who have been through various different traumas, have an impossible time seeing how one could ever still have faith in Jesus, in Christianity, because of everything they’ve been through, and the very strict versions of Christianity they’ve been taught. In one book, a football crime novel called Don’t Know Tough, a troubled high school football player thinks, in response to his coach encouraging him to find a “personal relationship with Jesus,” “Jesus, like Lebron James, or one of them big-time movie stars like the Rock. Them people are on another planet. How am I supposed to have a personal relationship with the Rock? With Jesus?” In the other book, Sacrificio, about an impoverished young group of Cuban counter-revolutionaries, the troubled main character remembers a Three Kings’ Day (how timely) years before—“He had told his mama [what] he wanted for Three Kings’ Day, much too old to believe in such fantasies anymore, magi bearing gifts for children…”

See, the Christianity these characters had experienced just didn’t make sense or connect with the difficulties in their lives. In both cases, these characters had clearly not learned about the Jesus as we are hearing about him today—a Jesus who is truly one of us. They only know the Christian theologies they have grown up with, and they only know the traumas they’ve experienced. And so in both of these cases, it’s impossible for them to believe that Jesus could ever be close enough to us to find comfort; it’s impossible for them to ever believe that a poor child would ever be honored by royalty. It’s impossible for them to see the world in new ways because an untouchable God and hardship are all they’ve ever known.

This problem is not unique to fiction. This kind of theology, this black and white thinking of a Jesus that is untouchable, that is so above us, seems sadly to be the norm in many places. In fact, in a conversation with one of you all recently, in talking about less open-minded faith tradition that this person grew up with, this congregant said that growing up they were told, ‘you believe what you’re told.’ That kind of faith leaves no room for seeing things in new ways, for seeing things in hopeful, exciting ways. That kind of faith leaves people wanting, leaves people trapped, believing that they’re not allowed to question, or to wonder. That kind of faith leaves no room for wondering what could inspire us like a dove and in this day, what could bring us hope and peace in difficult times.

But as we talked about on Christmas Eve, and as we can see from today’s passage, the Christian faith and the life of Jesus is full of beautiful, mind-bending contradictions that make it clear that anything is possible— that an all power savoir can at once be immortal, and can also be vulnerable and human. There is so much room in our beautiful faith tradition to be inspired to experience new things, to be moved to think more creatively.

Those two fictional characters are stuck in the despair of the status quo, stuck believing that this is just the way life is. And when we, in real life, us real people, are instructed to “believe what we’re told to believe,” we become trapped in that same way—resigned to a life of toil and sameness, told, essentially, not to think too deeply about things.

But think about the life of Jesus— we’ve already talked about his miraculous birth story—one that forces us to think about royalty, to think of saviors, to think of the divine in new ways, as a vulnerable human baby; today we come to the baptism—the story of the all-powerful Jesus, already known by many to be the savior, getting in the mud and water to be baptized alongside us, something a king of his time, or, let’s be honest here, our time, any time really, would ever do—and the stories that make of Jesus’ ministry are made up of parables and paradoxes, they’re made up of truths that broke all the rules of his day, that continue to break the rules of our day—Jesus did not want us to just accept what was told to us. Jesus makes it clear that though he is our savior, fully divine, that he is also fully human, and therefore one of us—that he is not untouchable on some other planet; that this human being, who received royal gifts as a baby, came so that each and every one of us would eventually be loved and respected and safe. Jesus, I believe, would weep at the idea that people shouldn’t think for themselves, that people should accept the world as is. And Jesus would especially weep at the idea that he is too far above us for us to truly feel his presence.

“Let it be so now,” Jesus says to John when he comes to be baptized, “for it is proper for us in this way to fulfil all righteousness.” This is a very peculiar comment from Jesus—because there’s nothing, anywhere in the Old Testament, nothing any ancient prophets ever said, that states that to fulfil righteousness, or justice, is this could also be translated, the savior must be baptized. But that doesn’t matter—because remember, Jesus is doing a brand new thing. To have a truly just world, we need a savior who gets down and dirty with us, who is truly with us.

And so in light of this new year, and in light of Jesus who constantly, thousands of years later, still inspiring us to see newly, to think differently, to do brand new things— let’s go into this new year inspired and excited— let’s find the Holy Spirit in whatever might be “like a dove” to us, and let’s spread this gospel of the mundane, the gospel every-human, this gospel of contradiction, this gospel of true righteousness and justice.

Let’s be the church in the world by making to clear to all we meet in this new year that just as Jesus stands in solidarity with each one of us, we stand is solidarity with one another. Amen.