The Blindness of Others

John 9:1-41

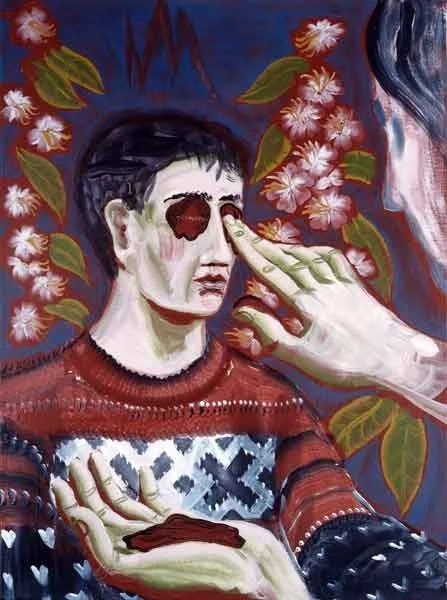

As he walked along, he saw a man blind from birth. His disciples asked him, ‘Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?’ Jesus answered, ‘Neither this man nor his parents sinned; he was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him. We must work the works of him who sent me while it is day; night is coming when no one can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.’ When he had said this, he spat on the ground and made mud with the saliva and spread the mud on the man’s eyes, saying to him, ‘Go, wash in the pool of Siloam’ (which means Sent). Then he went and washed and came back able to see. The neighbours and those who had seen him before as a beggar began to ask, ‘Is this not the man who used to sit and beg?’ Some were saying, ‘It is he.’ Others were saying, ‘No, but it is someone like him.’ He kept saying, ‘I am the man.’ But they kept asking him, ‘Then how were your eyes opened?’ He answered, ‘The man called Jesus made mud, spread it on my eyes, and said to me, “Go to Siloam and wash.” Then I went and washed and received my sight.’ They said to him, ‘Where is he?’ He said, ‘I do not know.’

They brought to the Pharisees the man who had formerly been blind. Now it was a sabbath day when Jesus made the mud and opened his eyes. Then the Pharisees also began to ask him how he had received his sight. He said to them, ‘He put mud on my eyes. Then I washed, and now I see.’ Some of the Pharisees said, ‘This man is not from God, for he does not observe the sabbath.’ But others said, ‘How can a man who is a sinner perform such signs?’ And they were divided. So they said again to the blind man, ‘What do you say about him? It was your eyes he opened.’ He said, ‘He is a prophet.’

The Jews did not believe that he had been blind and had received his sight until they called the parents of the man who had received his sight and asked them, ‘Is this your son, who you say was born blind? How then does he now see?’ His parents answered, ‘We know that this is our son, and that he was born blind; but we do not know how it is that now he sees, nor do we know who opened his eyes. Ask him; he is of age. He will speak for himself.’ His parents said this because they were afraid of the Jews; for the Jews had already agreed that anyone who confessed Jesus to be the Messiah would be put out of the synagogue. Therefore his parents said, ‘He is of age; ask him.’

So for the second time they called the man who had been blind, and they said to him, ‘Give glory to God! We know that this man is a sinner.’ He answered, ‘I do not know whether he is a sinner. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see.’ They said to him, ‘What did he do to you? How did he open your eyes?’ He answered them, ‘I have told you already, and you would not listen. Why do you want to hear it again? Do you also want to become his disciples?’ Then they reviled him, saying, ‘You are his disciple, but we are disciples of Moses. We know that God has spoken to Moses, but as for this man, we do not know where he comes from.’ The man answered, ‘Here is an astonishing thing! You do not know where he comes from, and yet he opened my eyes. We know that God does not listen to sinners, but he does listen to one who worships him and obeys his will. Never since the world began has it been heard that anyone opened the eyes of a person born blind. If this man were not from God, he could do nothing.’ They answered him, ‘You were born entirely in sins, and are you trying to teach us?’ And they drove him out.

Jesus heard that they had driven him out, and when he found him, he said, ‘Do you believe in the Son of Man?’ He answered, ‘And who is he, sir? Tell me, so that I may believe in him.’ Jesus said to him, ‘You have seen him, and the one speaking with you is he.’ He said, ‘Lord, I believe.’ And he worshipped him. Jesus said, ‘I came into this world for judgement so that those who do not see may see, and those who do see may become blind.’ Some of the Pharisees near him heard this and said to him, ‘Surely we are not blind, are we?’ Jesus said to them, ‘If you were blind, you would not have sin. But now that you say, “We see”, your sin remains.

I hate that I have to start my sermon out in this way—for two reasons—one, I really just wish some of this language wasn’t in the Bible at all. And two, I hate that I feel an obligation to talk about this before getting into the good stuff because of the horrific rise of antisemitism in this country, in the world, really, over the past few years. In the US, We’re currently in the midst of a five-year upswing in the number of antisemitic attacks and incidents. There are so many troubling reasons for this—from celebrities like Kanye West and Kyrie Irving spreading antisemitic conspiracy theories, to politicians, current and former alike, having dinners and functions with holocaust deniers and white supremacists.[i] This is why I feel the need to talk about some of the language the author of the gospel of John uses in this long and difficult passage (which, thank you for taking this on, Glenda!)

Verses 18 through 23 are the passages I’m referring to mostly, in which John switches from referring to the religious authorities as Pharisees into the even more blanket word, “the Jews.” It’s unclear why he does this, but to me, it makes very little sense—because every person in this passage is Jewish—Jesus, the blind man, his parents, the disciples—this is a Jewish community, so to use this language of the parents being scared of the Jews makes no sense. And let’s also remember that though John is writing as if he was with Jesus, the gospel of John came much later than Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and came pretty long after Jesus’s death and resurrection. So there are some pretty big anachronisms in here. When John says that the Jews, or the religious authorities were putting those who professed Jesus to be the Christ out of the synagogue—excommunicating them—this isn’t accurate at all. It certainly wasn’t accurate for Jesus’ day, and even in John’s day there’s not much, if any documentation that points to anything as extreme as excommunication for being a follower of Jesus; and furthermore, when this phrase “disciples of Moses” pops up in verse 28—this was never a term that Jewish people used to describe themselves, and the way it’s used here presents it very much in a way of making it seem as though disciples of Moses were less-than or just plain wrong, compared to disciples of Jesus.

Because John was writing so much later, the circumstances were certainly more tenuous in some ways than they were in Jesus’ day—because the Christian movement had been gaining momentum for almost a century at this point, there were surely schisms and tensions and arguments; that being said, it does seem that John is exaggerating some of this for dramatic effect, or maybe simple out of frustration, anger, who knows?

The bottom line is—is that these Jews, these Pharisees he’s referring to are better described as the religious authorities. They were men like Nicodemus who we discussed a couple weeks ago—powerful high priests who, despite still being part of the occupied Jewish people, were working more closely with the Romans, and clearly enjoyed their power and status quite a bit. So—for this sermon, I will be referring to them as the religious authorities, which is what they were. Now we can get to the actual sermon.

This passage is one about power vs. powerlessness; it’s about feeling ignored vs. feeling heard and being respected; it’s about feeling invisible and finally finding a place where you are truly seen.

And in line with allowing this blind man to be better seen, heard, and respected, I’d like to give him a name— last week I discovered the woman at the well was given the name of Photine by the Eastern Orthodox church; this week I discovered that both the Orthodox and the Catholic church have given this “blind man from birth” the name of Celidonius, and so I will once again borrow from their traditions for this sermon.

I found myself so frustrated for Celidonius from the very beginning of this passage. Here is this full-grown young man, just trying to live his life, presumably begging for money, trying to support himself any way he can in this unforgiving world he was born into, and Jesus’ blockheaded disciples walk by and see him and start wondering what he or his parents must have done for this man to be born with the disability of blindness. Jesus, thankfully, makes it clear that neither he nor his parents have sinned; he did nothing wrong to be born the way he was born. This ancient idea of younger generations suffering for the sins of the elders was something that Jesus was actively working against, it was something that made the new movement he was creating so beautiful and inclusive. It didn’t start with Jesus though; this belief was condemned way back in the book of Ezekiel— but this passage just proves how ingrained the most toxic beliefs can become.

Jesus heals Celidonius with nothing saliva and mud—and you’d think this would be cause for celebration—this man who has never seen can all of a sudden see. Truly miraculous, or rather, not a miracle, but a “sign” as they’re called in John. But after Celidonius is given sight, he’s just interrogated—again, and again, and again. First, his own neighbors are on his case— thankfully some people believe what they see—“it is he” some correctly confirm when they’re trying to figure out if this man who was blind and now can see is truly the man he claims he is. But others refused to believe it is, indeed Celidonius. If even says, that Celidonus kept saying—that word kept is crucial to me, he apparently had to repeat himself a number of times—“I am the man.” So presumably, many of his own neighbors are reducing him to his former disability, refusing to believe that he could be anything but the blind man they know and revile. The word kept shows up again—“But they kept asking him…” about how his eyes were open. So once again, the implication here is that he’s repeating himself, because his own neighbors don’t believe him the first, second, or maybe even third time he tells them his own true, lived experience.

It gets even more infuriating when the religious authorities get wind of this amazing sign performed by Jesus. They argue amongst themselves for a bit—some do seem to believe that Jesus is something of what he says he is due to these signs he’s performing—but the rest of the rigid authorities claim he’s not simply because he “worked” on the sabbath by making mud and ridding Celidonius of his blindness. And so the authorities first check in with his parents to get some more background. His parents confirm that yes, Celidonius is our son, and yes, he’s been blind since birth.” And then, his own parents throw him under the bus! This poor man is even disregarded by his own parents when they’re asked more question, “ask him, he’s an adult, leave us out of this,” they essentially say.

Finally, the religious authorities find Celidonius and ask him directly about what happened—‘Give glory to God!’ they say, which means “tell us the truth,” which Celidonius does, as he’s been trying to do all along—he gives them the facts: “I don’t know the guy who did this, all I know is that one second I couldn’t see, and then I could.” But they keep grilling him, and finally, after all this interrogation, he gets rightfully annoyed. He snaps a little. He makes it clear that he's already told them everything he knows, and then, my favorite part in the passage, he gives this sarcastic little job—“Do you also wany to be one of his disciples?” knowing that this would throw them off, knowing that this would finally turn the tides in some way. This is certainly risky—he’s a formerly blind beggar being investigated by some of the most powerful—not to mention stubborn and rigid—people around; he could be getting himself into so much trouble here.

But surely he’s just tired of being invalidated and disregarded, tired of being ignored, tired of being associated with only his blindness, tired of being unheard and unseen. He’s done. I imagine this experience he had is probably a microcosm of his life—a life spent with little agency because he was differently abled; a life spent fielding unsolicited speculation about what sins he or his family must’ve committed to end up the way he ended up; a life spent with parents who were never sure what to do with him; a live spent feeling invisible.

This is the story of man whose disability wasn’t his blindness— his disability was other people—other people’s blindness—their inability to see his humanity.

Celidonius tells the authorities off one more time—telling them the truth—that they know nothing about this healer, this man who is obviously from God, and yet they’re incorrectly assuming the worst of him, assuming Jesus is a sinner with because he took away a man’s blindness on the sabbath. Well, after the sarcastic comments, after they’ve been told some harsh truths that they can’t handle, the authorities drive him out of town—and they drive him right into Jesus’ arms. Jesus finds Celidonius, and Celidonius not only can see; but he finally feels seen. He finally feels respected, heard, and loved, and Jesus has gained another follower.

Unlike other miraculous stories in which the healed person immediately drops everything and joins Jesus, it takes Celidonius a bit—because I don’t think it was just the fact that he could now see that, but the fact that he realized that even now that he was abled-bodied, he’s still being undermined and invalidated. But Jesus recognizes right away that Celidonius is no sinner. He sees him, truly sees him. And I think Celidonius finally feels accepted and safe.

If we go back to the very first part of the passage, right before Jesus performs his healing sign, he says, “We must work the works of [God] while it is still day; night is coming when no one can work.” This is subtle foreshadowing of Jesus’ immiment death—while he is here, he is the light of the world, and so it is day, and they have to get as much done as they can—but the we here is crucial. Jesus is teaching his disciples how to heal, how to accept, and how to love; he’s showing them by example so they can continue his work when he’s gone.

Does this mean we’re expected to magically, physically heal people from their lifelong ailments or disabilities? No, it doesn’t—but as Jesus followers, as those who profess to live in the same Love and light that Jesus exemplified and preached, we can still do the work—the work of not ignoring our differently-abled sisters and brothers, the work of unconditionally accepting all to the table, the work of making sure everyone feels seen and heard and loved.

“Surely we are not blind, are we?” a couple of the religious authorities say at the end of this passage, maybe having some slight crisis of conscience finally. But they were—they were blind to the suffering of others, and even worse, blind to the humanity of others.

Surely we are not blind, are we? I challenge us to really think on that, to really think about what our blind spots are. I challenge us to work with our faith and our values to rid ourselves of those blind spots, and to see every person on this earth for the human being they are. I challenge us to make sure everyone we come across in life will feel loved and will feel seen. Amen.

[i] https://www.npr.org/2022/11/30/1139971241/anti-semitism-is-on-the-rise-and-not-just-among-high-profile-figures