The Challenge of Babel

Genesis 11:1-9

Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. And as they migrated from the east, they came upon a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. And they said to one another, ‘Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.’ And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. Then they said, ‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.’ The Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which mortals had built. And the Lord said, ‘Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.’ So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth.

Pentecost is the glorious, miraculous day when the Holy Spirit descended, and all of a sudden, for a moment, everyone, no matter their native language, could understand one another. Every person could listen and hear and communicate with no language barriers. Pentecost is one of the handful of previews in the New Testament of what could be if we would just do what we are truly called to do in this world.

But the story Nancy just read for us today is an ancient attempt to explain how language came to be. And it could be read as a punishment from God—a difficult lesson to be learned about the hubris of humankind. It could be read as a gift from God—the gift of diversity and cultures. It could be understood, uncomfortably, as a jealous and fearful God worried that their creation would someday surpass God’s own divine power. It could be simply interpreted as an early myth that we have moved beyond. I can’t tell you how to read this story, how to interpret it; there are truly so many options.

But one thing I can say confidently, is that this is a story of good intentions, and it’s a story of fear. God’s people wanted to shield themselves from what their destiny was all along—their destiny of venturing out to new places, becoming new and different people, experiencing new things. They wanted to build this spectacular tower for themselves, to make sure they would be God’s only favored ones, and they wanted to win God’s favor by building said tower and attempting to protect themselves from being scattered across the earth. What were they afraid of? Did they think if that if they did indeed scatter that God would lose sight of them? And so they were so desperate for God to never lose sight of them, and maybe also for themselves to never lose sight of God, that instead of spreading God’s love elsewhere, they decided it made more sense to cloister themselves in a tower just to be safe.

But we’ve known ever since the Greek myth of Icarus flying too close to the sun, trying to build or invent your way to the heavens never ends the way we hope it will. But in reading the story of the Tower of Babel this time around, I’m not seeing it so much as humankind’s hubris, but more simply of a kind of misunderstanding. Now, hubris absolutely plays into it—after all, one of the reasons they want to build this tower is because they want to “make a name for themselves.” But they seemed to think that physical proximity made them closer to God despite the fact that God is always with us, no matter what kind of exile or dark place we may be in. And more ironically than that, they apparently tried to build this fortress of a tower in order to not be scattered to foreign lands—but that very thing they were afraid of is what happened because of the building of this tower.

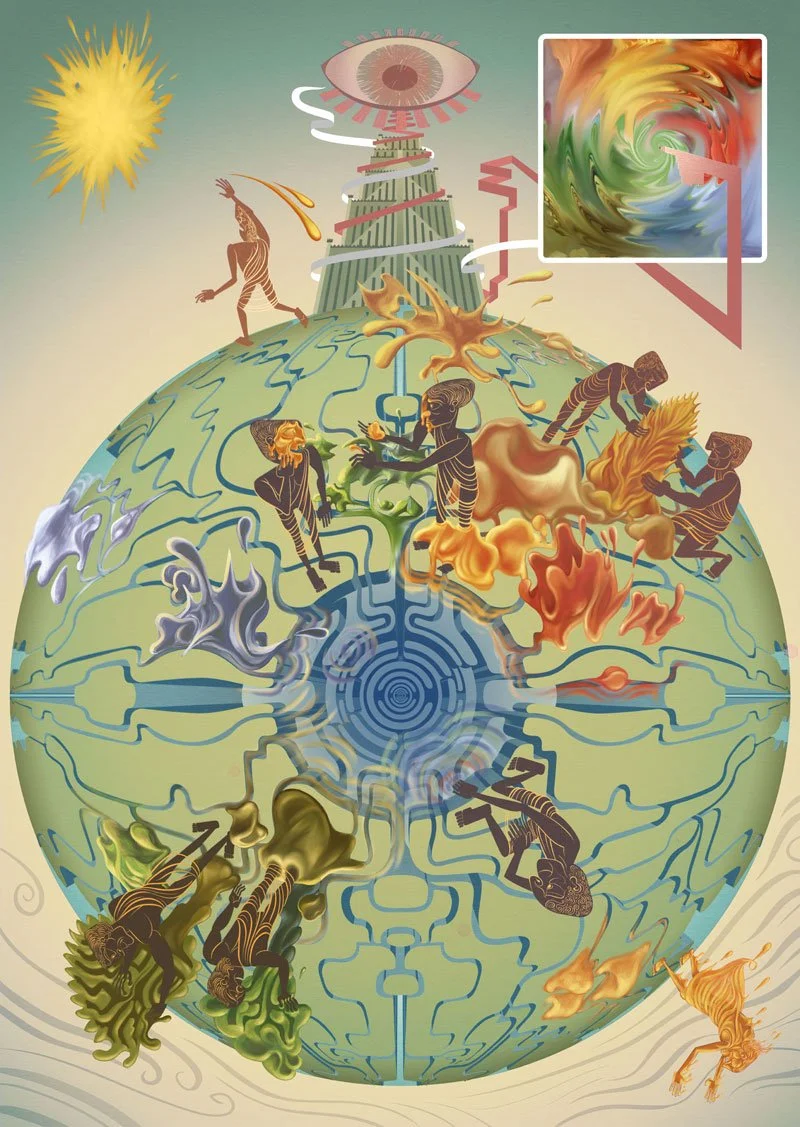

When I was a little kid and I thought of the Tower of Babel, I thought of this really tall, thin tower, I think I honestly thought of it more as Jacob’s Ladder, a completely different Biblical story that is indeed about a man climbing to the heavens and meeting God. But the Tower of Babel probably would’ve looked more like a ziggurat, an ancient Mesopotamian pyramid of sorts. Ziggurats were built, indeed to be a direct link between earth and the heavens. And they were also very exclusive. They were building as high as possible so that high priests and high priests only could escape flooding should a natural disaster occur; they were also built so that only priests and guards could easily get in. These towers were very exclusionary. They were built to keep things secret. They were built to keep rituals and riches for a small group of people. So in thinking of the Tower of Babel in this way, I’m thinking of this as the beginning of everything that would be wrong with the world—the beginning of secrets, of hierarchies, of class and caste systems; the beginning of attempts to keep the world small and closed-off. And then I think of the scattering of the people as less of a punishment and more of a challenge from God—a challenge that sadly, humankind as a whole, is not living up to.

There’s a book I read recently that I already quoted once in a sermon, the book is Pure Colour by Sheila Heti. There’s a part in the book in which two of the characters, Mira and Annie are having a conversation, almost a debate of sorts about family, about loyalty, about holding fast to traditions. Mira is the character with more traditional views, inferring that family, the people we are blood related to are the most important and that they should be prioritized above all else. Annie responds, “People should care for other people because they are familiar—because they’re also humans—not because they’re family.”[i]

And I wonder if this was God’s intention—I wonder if this was God’s challenge. I wonder if this was God’s way of showing the people that to be good, to be truly good, we can’t be one homogenous society, we can’t all be the same and only love one another because we’re related or because we look and act alike; we can’t stay cloistered and closed-off. I wonder if God wanted to show us that we have to love one another unconditionally, simply because we’re all human.

In the past few weeks, as the gun violence debates continue endlessly with no actual action of changes in sight, one of the things many people in power are doing is deflecting the blame and the cause of all this gun violence— those tired, old lines about the decline of “traditional family values” declines in religious attendance, divorce rates, etc., etc.—all this despite the fact that countries with much lower rates of religiosity don’t seem to have the problems that this country has. And I don’t think it’s accident that these arguments are resurfacing as educational and life-giving books continue to be banned from schools and libraries, as during Pride month, LGBTQ+ rights continue to be pushed back more and more. And the ironic thing is, it seems that in this society, those who claim to promote traditional, Christian family values are the ones who seem to be advocating for a closed-off, homogenous society that the God we’re reading about this morning put a stop to. It seems they’re advocating for a world in which everyone thinks the same way, in which everyone is beholden to the same, often oppressive values; a world that is closed off to anything that seems even remotely unfamiliar.

It's also interesting that, during June, during Pride month, you may hear a lot about found or chosen family—family that may not be related by blood, but they are family nonetheless. Family that had to be found because a family of origin didn’t love the way God requires us to love one another; family that had to be chosen because the family one was born into didn’t provide them with the unconditional love that we all deserve.

Thank God this past Thursday evening, our own town, hosted by this spiritual community, along with The Universalist Society, showed that unconditional Love with Hartland’s first ever Pride Walk. Church, let me tell you how beautiful it was to see around eighty people from this tiny town, marching, full of joy and love; and how beautiful it was to have such a warm welcome when we arrived here to cheers and snacks and extravagant welcome. Pride marches around the world have been going on for a long time now, and being a part of an open and affirming congregation like ours, where it has been made clear and obvious for so long that queer rights are human rights it may seem like we don’t need a Pride march. But as I’ve touched on in recent sermons, there is a very real and disturbing backlash happening throughout the country right now—from “don’t say gay” hysteria to further punishing the already small and oppressed trans community with bans on trans healthcare.

As people feel more able to be themselves, as people feel more free to come out of the closet, to be who they truly are, the more of an initial backlash there will be—why? What are people so afraid of?

I guess because we haven’t learned this lesson of the tower of Babel yet. I guess we want to hold onto our traditions of tribalism over unconditional capital-L Love of all people; over unconditional Love of all that is not just familial, but familiar to us; over the unconditional love that God calls us to act out in the world. We’ve been failing this challenge for a millennia, church; and these days tribalism and division are worse than ever.

I read a really lovely article last week about a queer couple who moved from New York City back to their hometown of Salt Lake City during the pandemic. They had planned on just riding out the pandemic there, but once the pandemic began to wane a bit, before they moved back to New York, they decided to try something in this generally less queer-friendly area than what they had become accustomed to in New York City. They decided to start a queer Sunday night dinner. As the article states,

In Utah, where Sunday dinner is ingrained into the culture, no other day seemed as appropriate to Madden and Swayne. Sunday dinner was something they felt they could reframe for a queer community that may have negative associations with the practice. They wanted to fill their home with queer joy.

Another perfect example for this Communion Sunday of Pride month. We know everyone is welcome at the table here, but sadly, in so many places, that just isn’t the case for queer folks. One regular attendee of these Sunday night dinners is quoted as saying “There’s no place like this anywhere.” The article states that “…nothing outshines the chosen family that gathers at Iowa House for Sunday dinner.”[ii]

This Sunday night dinner in Salt Lake that this couple started has clearly become something sacred for so many who have felt abandoned or forgotten or exiled. It has become a church for them. And despite the fact that many of these attendees are people who have left or been excommunicated from their Mormon faith, these are the people who are meeting the challenge that God has given us—these are the people who are realizing that the love is not just in familial but in the familiar— the familiarity of all humans, who can come together, whether or not they are related by blood or race or religion or orientation. These people who have been betrayed by a belief system that professes to believe in love, are the ones who are really showing what capital-L Love is all about.

As is so often the case, it is the people who are oppressed, the people who are on the fringes, the people who have been told they weren’t living the right way, who are exemplifying God’s extravagant welcome in the world. As is often the case, it is the people some of the loudest in power would try to call deviant or wrong who are living up to the challenge of Babel that God set for us.

One of the founders of these Sunday dinner, Jade Swayne, says of growing up queer and going to an anti-queer church, “there was always this overhanging dread around my identity…”.[iii] How heartbreaking that in places of worship people are still made to feel a sense of dread about just being who they are. Swayne says that now that they have left the church, they feel that can finally fully be themselves.

Church, I know we’re already open and affirming. I know we can sometimes take for granted how welcoming this community is. And I think there’s actually something really beautiful in that, that it feels so natural and obvious to us to welcome all unconditionally as God calls us to do. But the fact is, this is not the case elsewhere, and the fact is, Christian places of worship have a pretty bad track record when it comes to queer joy and Love.

So yes, thank God we are mostly living up to the challenge God has set for us; but let’s continue to challenge ourselves. Let’s look for and think of new ways to care for and love one another, new ways to show radical and extravagant welcome. Let’s really listen to one another; let’s really hear one another. Let’s demolish language barriers, barriers of all kinds. Let’s meet the challenge of Babel head-on. Amen.

[i] Sheila Heti, Pure Colour (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022), 189.

[ii] https://www.sltrib.com/artsliving/2022/05/29/iowa-house-queer-utahns/

[iii] https://www.sltrib.com/artsliving/2022/05/29/iowa-house-queer-utahns/