We Have to Celebrate

Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

Now all the tax-collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, ‘This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.’

So he told them this parable:

Then Jesus said, ‘There was a man who had two sons. The younger of them said to his father, “Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.” So he divided his property between them. A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and travelled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need. So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything. But when he came to himself he said, “How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.’ ” So he set off and went to his father. But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. Then the son said to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.” But the father said to his slaves, “Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. And get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!” And they began to celebrate.

‘Now his elder son was in the field; and when he came and approached the house, he heard music and dancing. He called one of the slaves and asked what was going on. He replied, “Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.” Then he became angry and refused to go in. His father came out and began to plead with him. But he answered his father, “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!” Then the father said to him, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.” ’

Here’s a fact I didn’t realize until last year—Sundays don’t count as part of Lent. Lent is actually 46 days if you count the Sundays, but you don’t! Sundays are always a feast day, so if you gave up chocolate, have some chocolate today! If you gave up fried food, go have some fish and chips. If you gave up swearing, go ahead and curse to your heart’s desire.

Lent is such a solemn time. Holy Week is in less than a month, and we’re coming upon that time of betrayal, despair, and violence. And in our own tradition, with its Puritan roots, we can sometimes be a little too serious, a little too somber. And I say this as very reserved New Englander who absolutely loves the quiet, contemplative humanity of Holy Week. But there has got to be some room for not just forgiveness, but also for joy. There’s got to be some space for finding some joy and celebration in all this grief and chaos.

You may be wondering why I’m up here seemingly encouraging hedonism during Lent, why I seem to be inspired to say all this by a scripture passage that seems to be about repentance. Well first of all—remember, it’s not Lent. It’s Sunday, so we’re technically not in Lent right now. Second of all, I really wanted to focus on the joy of this passage—I wanted to focus on the party! This is maybe the most famous of Jesus’ parables. It’s famous for a bunch of reasons. It’s the longest parable, and because of that, it’s really easy to understand—there’s a beginning, middle, and an end. It’s a very palatable, relatable message. While it’s easy to understand, there are a million different directions one can go with it—you can go allegorical, the father is God, the prodigal son is Israel, or the prodigal son is your average sinner; you can take this as very literal and really dig into all the cultural and legal issues of wills and inheritances… the list goes on and on, there is so much to choose from. It’s overwhelming for a preacher, and daunting.

And during this solemn Lenten time, during this time of war and division, during this time of freezing temperatures when all we want is Spring, I wanted to focus on the joy from this passage. I wanted to focus on the unconditional love and joy that we all so desperately need right now. I want to focus on the positive and the unexpected. Because the unexpected was what Jesus was all about—this parable is the third and final in a slew—and as Sue read, the parables begin with a few ultra-serious, self-righteous Pharisees criticizing Jesus for sitting down to meals with so-called sinners. And Jesus shocks them by telling them this story about a hard-partying, irresponsible son whose father offers him unconditional forgiveness… and a party.

Now, I don’t want to trivialize Lent here—but I do believe we all need a break. I think it’s telling that it seems to surprise so many people that Sundays technically do not count as Lent. Why do we want to suffer more than we have to? What good will that do? Last year, while we were still in full isolation, I talked at length about the fact that that Lent was the Lentiest Lent ever, and I encouraged not actually giving up anything since we were sort of forced into a Lenten journey of deprivation. And sure, things aren’t back to 100% this year, but it’s certainly better than it was last year. Even so, we deserve a break. We all deserve a break sometimes.

Last week, remember we talked about the fact that productivity has skyrocketed, but worker’s compensation, and just general quality of life has not. We talked about that despite the fact that the system is broken, that the system is rigged— normal, hard-working people who can’t afford basics like food or shelter, are looked down upon, are judged, and are thrown to the wolves. While last week I cited advancements in technology as the reason this has all been so exacerbated, this is not a new thing—not even close. Many of you have probably heard of the theological, sociological concept of the Protestant work ethic, coined by late nineteenth and early twentieth-thinker Max Weber; it’s also known as the Puritan work ethic. It could be said that our country, especially since the industrial revolution, was built on this idea of the protestant work ethic. Without going into all the controversial stuff about predestination, the Protestant work ethic is essentially the idea it’s not just clergy who have a calling from God—everyone has a calling and that calling is whatever job you’re doing at the time, and that you should work diligently and humbly. In some ways, this is lovely— we could relate this to Martin Luther King Jr’s street-sweeper speech: “If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music, or Shakespeare wrote poetry,” King said. We could relate this to Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians—that we all have our place in this world, in each of our communities, and no one person is any less than the next; we all must work hard and work hard together and help one another if we want a functioning society in Christ.

While those idea are all well and good, it’s unfortunately not really what came out of this Protestant work ethic. What came out of it is essentially the fact that all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. What has come out of the Protestant work ethic is this idea that, as we talked about last week, if we don’t keep our heads down, work hard, save our money, live a quiet happy life, then we’re not worthy of the love and support we need to really thrive as relational humans in this world. That’s why Max Weber concludes that despite its well-meaning beginnings, total adherence to this Protestant work ethic traps in what he calls an iron cage—a sad and gray place where we work because society says it’s good for us to work, not because we’re actually changing the world for the better, and not because it actually brings us any joy.

So when this hedonistic prodigal son has had is fun, has sown his wild oats, has blown all of his money he all of a sudden realizes, “oh no… I’ve forsaken everything that was actually important for a good time.” He has this horrible crisis and he believes he’s blown it. Now, it should be noted that everything the son did in this parable was actually a pretty big deal—taking your inheritance before your father died was uncommon and frowned upon; and him taking the inheritance and blowing it was breaking commandment number #, honor your mother and father. To make matters even worse, the son’s behavior would have brought shame upon the family, and the community would have been gossiping and harshly judging this family. Even though all this is true, the father doesn’t care. He runs out to meet his broken and ashamed son as we makes his way back. And remember as Sue read, that the son has this sort of internal monologue deciding what he’ll say before he goes back to his family: “I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.’” (Now, this could easily be interpreted as just an opportunistic, disingenuous plea to get some food, but let’s give him the benefit of the doubt). So when he gets home, he starts this line he practiced, but his dad doesn’t even let him finish. Because his dad was going to love him and accept him and welcome him back no matter what. He didn’t even have to finish his repentance, he didn’t have to specify that he should be treated as a hired hand rather than a family member; in fact, he didn’t even need to do anything to convince his dad that he was being real or genuine! Because it’s not necessary. To the father in this story, his son, prodigal or righteous, doesn’t matter, was always his son, would always be his son, will always be his son.

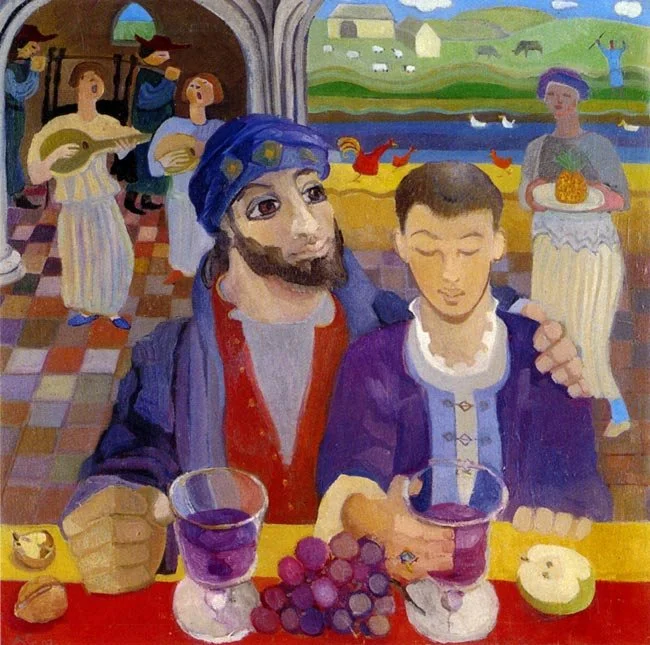

Now onto the party! So it’s a big deal that this father decides to slaughter the fatted calf—not only was this for special occasions, but slaughtering a whole fatted calf was enough to feed the entire community, and I really love to imagine that that was his exact intention; it makes this whole situation even more beautiful—not only does the father unconditionally accept his son back into the fold, but disregards the community’s judgement by in turn, not judging them at all, and inviting them to this feast to celebrate the return of this wayward child. It’s such a joyful way of changing people’s views, of making it known that just because someone makes a mistake doesn’t mean they aren’t deserving of love, or a party.

Now, enter the older son—I think most of us can relate to him, as miserable as he may seem in this story. He sees this huge party in honor of his little brother who squandered everything he worked hard to keep. He did everything right by society’s standards. But the disconnect here, I believe, is that he sees his little brother being honored with a party celebrating his return as sort of a punishment for him; I think he sees this as taking away from his hard work and accomplishments. But nothing has actually changed for this responsible older son. “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours,” I imagine his father saying so kindly, reminding his son that he hasn’t suffered, and not only that, but he will get everything he deserves—his father’s land, his whole inheritance, safety, stability, comfort… none of this is going away just because his little brother gets this party as a reminder that he is loved, and that he still deserves love and joy in spite of his dalliances or mistakes.

You know, it kind of brings to mind for me, that harmful notion that someone who gets government assistance shouldn’t use that money to buy a new TV or that they shouldn’t use their SNAP benefits to buy a nice steak once in a while— because everyone deserves love, and everyone deserves some joy. Everyone deserves to enjoy life, and we can’t punish ourselves, and we can’t punish one another for not living the type of life this society deems as “right” or “moral,” because, as we talked about last week, this society equates morality with wealth, and this is just plain wrong.

The culture that the Protestant work ethic has created is kind of joyless! It’s a culture that revolves around work, frugality, and solemnity, that revolves around keep your head down being productive, even if that productivity isn’t bringing you joy or doing a whole bunch of good in the world. It’s a culture that revolves around self-flagellation and guilt if we’re not “productive,” or if we make mistakes. It’s the opposite of so much that Jesus taught— working for the good of the whole, not just ourselves; and forgiveness, love, and joy.

Now after the father reminds this cranky, wet-blanket, older son that he will still have everything he will ever want or need in the world, he says, “…we had to celebrate and rejoice.” Not “we should,” or “we can;” “we had to.” There was no choice here. When someone who is lost and wandering, when someone who has made mistakes makes his or her way back home, we have to celebrate, no matter what their reasons were for leaving or messing up in the first place. This younger brother suffered. He was almost starving. He was ready to go back home and be punished and suffer even more. But what good would that do? What would that teach us about the unconditional love that we receive from God, that we are called to emulate? So we have to celebrate.

So whether or not you gave up something for Lent, whether or not you’re happy with how your life is going, whether or not you’re mad at yourself or someone else for things not going the way you wanted or planned, give yourself a break. Give others a break. That’s what Sundays in Lent are for, after all—to give us a break from the fasting, from the deprivation. Sometimes, we just have to celebrate. Amen.