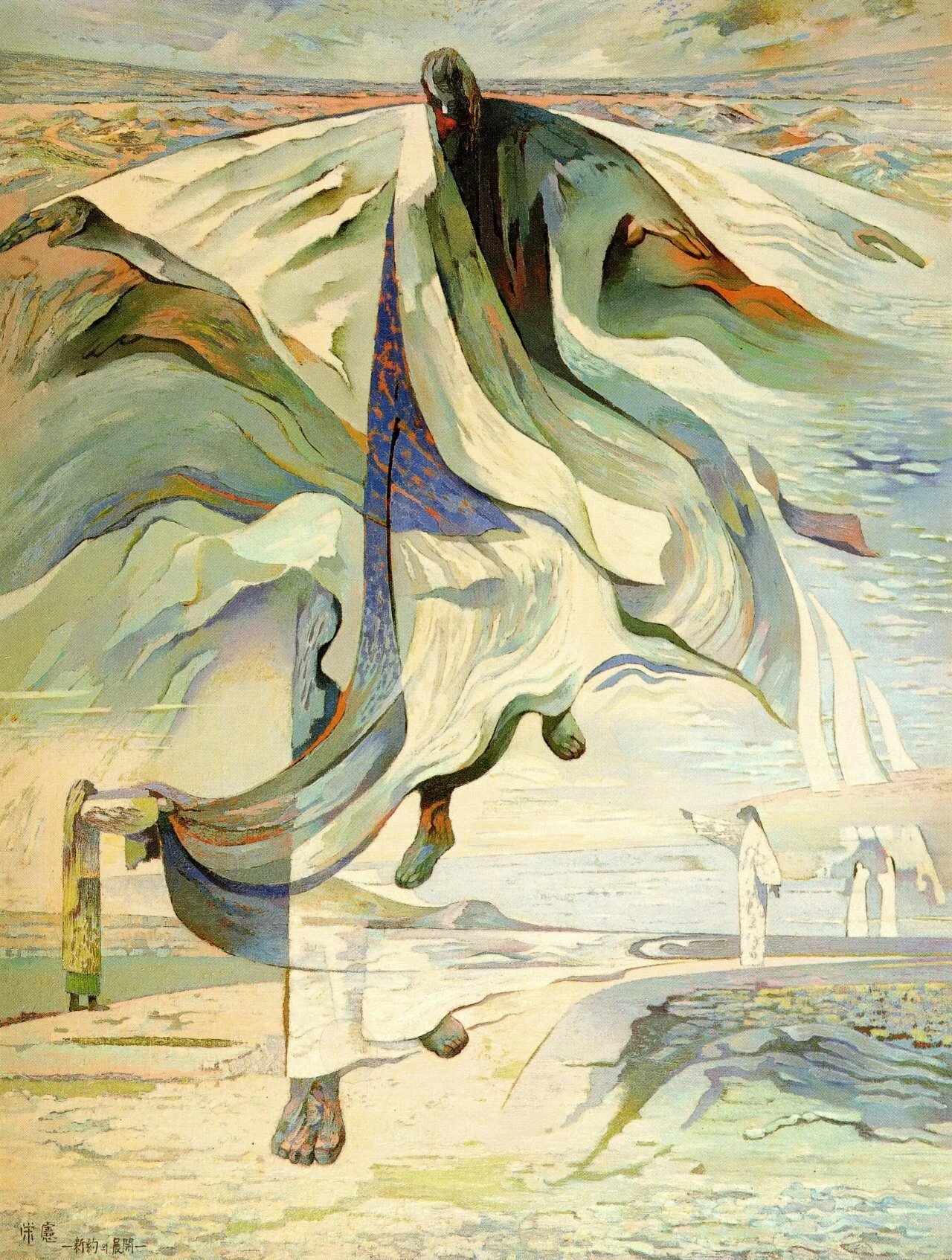

With Arms Outstretched

1 Kings 8:1, 6, 10-11, 22-30, 41-43

Then Solomon assembled the elders of Israel and all the heads of the tribes, the leaders of the ancestral houses of the Israelites, before King Solomon in Jerusalem, to bring up the ark of the covenant of the Lord out of the city of David, which is Zion. Then the priests brought the ark of the covenant of the Lord to its place, in the inner sanctuary of the house, in the most holy place, underneath the wings of the cherubim. And when the priests came out of the holy place, a cloud filled the house of the Lord, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house of the Lord.

Then Solomon stood before the altar of the Lord in the presence of all the assembly of Israel, and spread out his hands to heaven. He said, ‘O Lord, God of Israel, there is no God like you in heaven above or on earth beneath, keeping covenant and steadfast love for your servants who walk before you with all their heart, the covenant that you kept for your servant my father David as you declared to him; you promised with your mouth and have this day fulfilled with your hand. Therefore, O Lord, God of Israel, keep for your servant my father David that which you promised him, saying, “There shall never fail you a successor before me to sit on the throne of Israel, if only your children look to their way, to walk before me as you have walked before me.” Therefore, O God of Israel, let your word be confirmed, which you promised to your servant my father David.

‘But will God indeed dwell on the earth? Even heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built! Have regard to your servant’s prayer and his plea, O Lord my God, heeding the cry and the prayer that your servant prays to you today; that your eyes may be open night and day towards this house, the place of which you said, “My name shall be there”, that you may heed the prayer that your servant prays towards this place. Hear the plea of your servant and of your people Israel when they pray towards this place; O hear in heaven your dwelling-place; heed and forgive.

‘Likewise when a foreigner, who is not of your people Israel, comes from a distant land because of your name —for they shall hear of your great name, your mighty hand, and your outstretched arm—when a foreigner comes and prays towards this house, then hear in heaven your dwelling-place, and do according to all that the foreigner calls to you, so that all the peoples of the earth may know your name and fear you, as do your people Israel, and so that they may know that your name has been invoked on this house that I have built.

A few weeks ago, during our first Sunday back here in the sanctuary, we talked about how this building isn’t for God, but rather, for us. The scripture passage for that week was one in which King David believed the time had come to finally build God the grand temple that was prophesied. But God chastises David and lets him know that is not for him to decide. David will be an ultimately great ruler, yes, but he will not be the one to build the temple. His wise son Solomon will be the one. And this brings us to today—the temple is built and it is being dedicated with lots of pomp and circumstance and a long prayer imploring God to always listen to their people, but especially when they are praying in or towards the temple.

When I preached on that passage from 2 Samuel, I did cheat a little and skipped ahead to this passage, to Solomon’s rhetorical question in which he says, “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? Even heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you, much less this house that I have built!” These buildings can’t possibly contain God. That’s why they’re for us and not for God; and they exist for us in the sense that these are sanctuaries where we can come to feel heard, where we can come to pray, where we can come to think and to wonder and to wrestle and to feel safe and not be judged.

Because even though the bulk of this passage is a dedication and a prayer to God, it’s just as much, if not more so, directed to the people. There are all these reminders in this passage, about God’s covenant with the people—but God never needs a reminder. It’s the people who need reminders, it’s us. For so long the Israelites had been wandering without a home base. For so long they had to make do with what they were given, worshipping in occupied lands, hiding their beliefs, wandering the desert. Now they finally have a place where they, not God, can focus on the covenant, this love. They finally have a place where they can worship freely, a place where they can, for a time, put aside the worries of the outside world and focus on peace and comfort, and safety with God. So I wonder if they needed some practice. I wonder if they needed this long prayer from Solomon to remind them what this temple was for—that this temple is the place where you can dedicate your time, your mind, your energy to prayer and to God, that this is the place where God will “hear the plea of [God’s] servant and of [the] people Israel when they pray towards this place.”

As we’ve talked about before, and as we’ve seen over this past year and a half, we know God can hear us regardless of where we are. We know this building isn’t necessary to feel the presence and the peace of God. But we also know that it helps. We know that in a world full of noise and distractions this is a place where we can escape and focus. We know that in a world full of violence and insecurity, this is a place where we can go to feel safety and comfort.

A few weeks ago, we talked about how we surely feel so much comfort and peace being back here in the sanctuary, masks or not—knowing that we are vaccinated, knowing that despite two steps back here and there, we are, God-willing, inching back towards some sense of normalcy, some sense of safety. It feels familiar and good, but it also feels a little different, doesn’t it? It feels both familiar and unfamiliar, it feels both comforting and maybe a little scary for some people. So I think, like Solomon’s people, we might need a little reminder of why we’re back here; a reminder of what this space is truly for.

We’re not just here for our own safety and our own comfort. This building exists to be a safe haven to any and all people. After the Israelites dealt with worshipping in occupied lands, I wonder if they had some reservations about allowing people not of their own culture into their lands, into their place of worship. I wonder if they, at times, felt a little less than hospitable. It would make sense that they might, and so I wonder if that’s why Solomon emphasizes welcoming the foreigner into the temple. “Likewise when a foreigner, who is not of your people Israel, comes from a distant land because of your name —for they shall hear of your great name, your mighty hand, and your outstretched arm—when a foreigner comes and prays towards this house, then hear in heaven your dwelling-place, and do according to all that the foreigner calls to you…”. Here is the kind and wise Solomon imploring God to hear the prayers of all people, regardless of where they come from, or where their beliefs once lay or even currently lie. And here also is Solomon letting his people know that gatekeeping is not allowed. Here is Solomon letting his people know they must invite the foreigner in with open arms, with outstretched arms like those of their loving God.

Now Church, with this emphasis on foreigners in this passage, I couldn’t help but think of the heart-wrenching stories over the past week about the lightning-fast fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban. I couldn’t help but wonder why so many restrictions of refugee status for the Afghan people remain in place. I couldn’t help but wonder why no plans seem to have been put in place to safely evacuate these frightened and powerless people to safety. I couldn’t help mourn the fact that this country doesn’t seem to have its arms outstretched to those in need anymore— especially towards those whose lives have been directly affected by us—by this two-decade long war. I read a novel a few months back by the author Phil Klay, who, in addition to being a writer was also a Marine and veteran of the war in Iraq. At one point in the book, the narrator, a journalist living in and reporting from Kabul, Afghanistan writes of a phone conversation she has with her mother, in which her mother very abstractly, very casually, notes that things look a little dicey over in Afghanistan, and how is her daughter doing? The narrator’s response to the reader is, “Because to her, to my mom, a woman who follows the news, who is smart, who is interested in foreign policy, who has a…daughter living in Kabul, this is certainly terrible but also just what happens over there.”[i]

What a perfect encapsulation of why we need reminders of what this church stands for, of what this country should stand for. I’m certainly not here to talk about foreign policy, or make any judgements on the actual withdrawal of troops, or what, if anything could have been done differently. But what I do know now, what is clear as day right now, is that there are people in need, there are people in grave danger, many of whom trusted and put their faith in the American military, many of whom worked as translators, as soldiers, and there just don’t seem to be any adequate systems in place to get those people out of danger. I think right now, for the first time in well over a decade, these problems abroad—these crises that we’ve always just thought of as something that just “happens over there—” that they maybe feel a little closer to home than they did before. I think maybe things seem a little less abstract now that we’re seemingly able to watch the fall of a country in real time—the fall of a country directly related to decades of meddling and invasions by so many developed nations.

There have been many articles about history repeating itself, with comparisons to the fall of Saigon during the Vietnam war. But one stark difference is this—this is from a recent article in the New York Times:

After the war in Vietnam, a bipartisan consensus and collective sense of moral responsibility helped provide the framework for Operation New Life, which swiftly evacuated 130,000 vulnerable, mainly Vietnamese, people to a makeshift refugee camp on the island of Guam. From there, they were processed and moved to temporary migration centers across the United States. Over the course of years of sustained efforts, 1.4 million Vietnamese people eventually settled in the country. Now, the United States is trying to provide safety for a far smaller number, and has struggled in that effort.[ii]

So I’m standing here wondering— what happened to our “collective sense of moral responsibility”? What happened to greeting the suffering foreigner with arms outstretched, as commanded by God?

This has been a heavy week, hasn’t it? Between Afghanistan, Haiti, the Delta variant ripping through so much of the world, it’s another week of feeling a little helpless. It’s another week of one humanitarian crisis after another. And as always, I don’t expect this little UCC church in Vermont to come up with a genius foreign policy plan for the middle east, a brilliant infrastructure plan for Haiti, or some kind of miracle drug that will eradicate this virus. But I know that the people in this congregation, and in this community know how to be the church out in the world. I know the people in this building, the people zooming in, know how to be welcoming and kind to all people. I know this congregation has something that’s very rare these days—a collective sense of moral responsibility. The very fact that I’m looking out into a sanctuary of masks is evidence of this collective sense. It’s a small but crucial outward gesture, as I wrote about in my note to the church in the newsletter this week, that makes it clear we welcome all—including those who cannot yet be vaccinated, including those who are still understandably nervous about being back out in the world in indoor spaces.

I know this church does and will continue to do big and great things for this community. But we have to make an effort to not get bogged down by despair of such a harsh world, and know that we can do the work of God in small but crucial ways every day. We can continue to make sure this sanctuary is truly a sanctuary—a place of refuge. We can continue to make sure that this is a place where we welcome any and all with open arms; a place where no prayer is too small or too idealistic or too naïve; a place where anyone can pray or question without fear of judgment.

As we move forward from this day, and from this difficult week, I want us to think about the many different ways we can invite the foreigner in, especially with welcome Sunday coming up—the many different ways we can make sure all feel safe and welcome within these walls, as well as in the greater community. It’s really hard in such a divided world. And Vermont, for all its progressive and compassionate values can be a pretty insular place; it can be a little intimidating, a little hard to break through.

So I hope we go from today really thinking about Solomon’s prayer, his temple dedication. I hope we know that each and every one of us is welcome here, is welcome to be here in this place to focus on worship in whatever ways that make sense to us. And when we think about how comfortable, how safe, and how unconditionally accepted we are, how loved we feel, especially within these walls where we have the time to focus on God’s love, let’s make sure we extend these feelings to all—the foreigner, the outcast, the frightened, the oppressed—as God does: with outstretched arms. Amen.

[i] Klay, Phil. Missionaries: a Novel. Penguin Press, 2020. Loc. 547 (kindle edition)

[ii] https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/08/18/world/taliban-afghanistan-news