Sea to Sea

John 12:12-16

The next day the great crowd that had come to the festival heard that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem. So they took branches of palm trees and went out to meet him, shouting,

‘Hosanna!

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord—

the King of Israel!’

Jesus found a young donkey and sat on it; as it is written:

‘Do not be afraid, daughter of Zion.

Look, your king is coming,

sitting on a donkey’s colt!’

His disciples did not understand these things at first; but when Jesus was glorified, then they remembered that these things had been written of him and had been done to him.

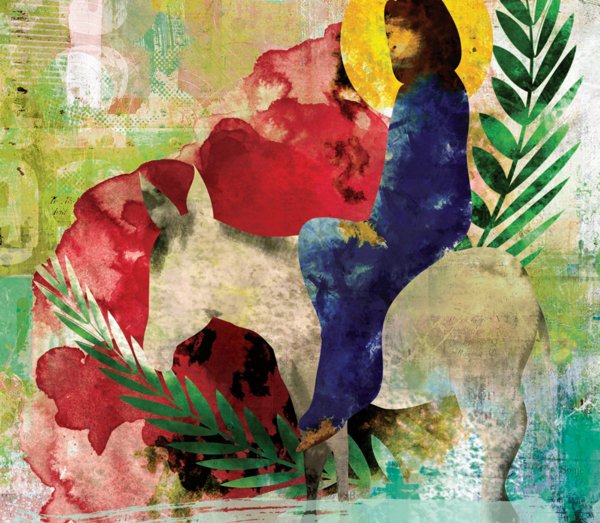

When I preach on a gospel story that’s told in multiple gospels in different ways, I try to find what’s unique about the one I’m preaching on. I try to figure out what this passage is saying that the others don’t emphasize; or what is left out of this version that’s focused on in the others. In the case of John’s version of the triumphant entry into Jerusalem, it’s not… especially triumphant. It’s pretty subdued; there’s very little detail. Unlike in the synoptic gospels, there are no mysterious instructions on how the disciples must find a colt for Jesus to ride on. In John’s version, it’s just Jesus, seemingly going through the motions, finding a donkey on his own, no drama or suspense. The main focus in John’s version isn’t even on the entry, in my view—it’s on the Old Testament reference from prophet Zechariah; it’s on the reference to Psalm 118. “Jesus found a young donkey, and sat on it, as it is written…”

And it’s written in Zechariah 9:9-10, which I’ll read for you now:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion!

Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem!

Lo, your king comes to you;

triumphant and victorious is he,

humble and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

He will cut off the chariot from Ephraim

and the warhorse from Jerusalem;

and the battle-bow shall be cut off,

and he shall command peace to the nations;

his dominion shall be from sea to sea,

and from the River to the ends of the earth.

So the passage that John references so clearly is all about this prophesied and mysterious king coming to disarm the nations; it’s all about this new leader coming to create peace from one end of the earth to the other. And the subdued and subtle nature of John’s version, to me, really accentuates the humbleness, and the peace that Jesus is trying to usher in, not just to Jerusalem, but to the world. The donkey he rides on is in direct contrast to the chariots and warhorses of the day, showcasing the ruling class’s riches, might, and this kind of hypermasculine power. It’s subverting what people thought of as leadership in Jesus’ broken world; it’s subverting the idea that to be a successful leader, you have make people fear you, you have to intimidate people with material riches, weapons and physical strength.

When I came to the realization that John’s version of Jesus’ entry intro Jerusalem was emphasizing humility and peace, it was impossible not to think about the violence going on in the Holy Land right now, as we speak. I saw a photo last week of a Palestinian family fleeing the area surrounding the Al-Shifa hospital, sitting on a small trailer being dragged away from their shelter, by, of all animals, a donkey. At that point the hospital had been under siege for several days, with offense claiming to have secured weapons and killed terrorists, and the defending side stating that only patients and civilians using the hospital as a shelter had been killed.

And when I read Zechariah chapter 9, verse 10, and read that this peaceful king’s “dominion shall be from sea to sea, / and from the River to the ends of the earth,” I immediately thought about what has become a pro-Palestinian freedom cry “From the river to the sea.” This cry has become quite divisive, as some claim that it’s Hamas’ battle cry, and they have indeed attempted to appropriate it for their own violent means, but the origin seems to come from the 1960s, over 20 years before Hamas existed, and it alluded to going back to the original 1948 borders when Israel was first established, and Jews and Arabs lived side-by-side.

But the point here is not to get bogged down in semantics. I was conferring with a good friend of mine, my resident Jewish friend Dan who I’ve mentioned in sermons before, about this direction I was planning on going in with this sermon, and he warned me against using this this river-sea parallel saying not to get bogged down in what it means or where it started, because that’s what the violent want— they want us to be arguing about words, they want us to get into a he-said-she-said so we’re distracted by the actual atrocities that are happening. Because the way I see it, both Zechariah verse 10 and “from the river to the sea” are simply saying that we want freedom and peace as far as the eye can see—we want an end to sieges on hospitals, and end to people being displaced from homes, an end to this lopsided offense.

I didn’t realize how much my brain chemistry would change from having a baby. I didn’t realize how much harder pictures of crying and injured children would hit after I had Frankie. And as of last week, over 13,000 Palestinian children have died. 13,000. And my heart hurts every time I see a picture of a child in pain, and there are just so many coming out of Gaza every day.

In just a few minutes, we’ll hear the Markan story of the Last Supper and the Passion, the end of Jesus’ public ministry— but just a few chapters before, as Jesus is in the midst of his ministry, with the crowds growing, he makes the famous comment, “Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.” And he says this after his own disciples rebuke him for sinking so low as to bless children. A couple years ago, I preached a sermon about the radicalness of Jesus lifting up children, not because of anything that has to do with innocence, or purity—but rather because, in Jesus’ day, children were looked upon as below, as not human. They were on the same level as beggars, widows and other poor folks who were unfairly vilified or disregarded by society as less-than-human. Because that’s how we get to this point, right? Where we can shrug our shoulders in the face of war crimes, because those in power have trained us to see those who are being bombed and exiled as less than human.

And so, Jesus enters into Jerusalem on a donkey, as the peaceful leader Zechariah hoped and prayed for. And he does this to be one with the least of them. He does this so he, though divine, is on the same level as the children, the widow, the lowliest of all. He does this so he is approachable, accessible, instead of untouchable and intimidating, high on a chariot dragged by a warhorse. He does this because he is indeed human, and so are the children, the widows, and all of those whom society deems less than.

He is one with the children of Gaza as they are driven and bombed out of their homes. He is one with the families fleeing in a cart dragged by a donkey through the rubble. He is one with those protesting and fighting for this country to stop arming the aggressor with a proposed $14 billion in weapons for their wildly disproportionate response to the October 7th attacks. He is a leader who brings subtlety, who brings compassion, who brings peace. As the fighting goes on, as we see the warlords of the world winning again and again, I pray that we can still learn from Jesus’ peaceful entry on a humble donkey. I pray that this country will stop aiding in unjust wars abroad, and I also pray that this country does more to keep the people here at home safe from violence.

We may not have warhorse-drawn chariots, it does indeed seem that those with the loudest voices, the biggest cars, the sprawling mansions, and the most deadly guns are the ones who make news, are the ones calling the shots—and the powerful who purport to be Christians just go along with it, apparently completely forgetting the fact that Jesus came into Jerusalem, not in a cybertruck or a limousine, but quietly, humbly, on a donkey, on the same level with those who were cheering Hosannah—save us! to him as he rode in, feet nearly grazing the ground, as Kate Bowler wrote for our call to worship today. Jesus came to usher in a quiet peace, one that no one yet understood, not even his disciples; and sadly, it’s still deeply misunderstood today.

And so, as we enter into Holy Week— as we enter into that quiet time of contemplation and sorrow, as we walk with Jesus on his road to Gethsemane, as we continue to be bombarded with images of war and violence in our world all the while, we will continue to hold out hope that people will eventually understand what it was all for; and we will continue to do the work to help people to understand it—and we will have the peace that Jesus marched and died for at long last. Amen.