The Mystery of Perfection

Hebrews 5:5-10

So also Christ did not glorify himself in becoming a high priest, but was appointed by the one who said to him,

‘You are my Son,

today I have begotten you’;

as he says also in another place,

‘You are a priest for ever,

according to the order of Melchizedek.’In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission. Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him, having been designated by God a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek.

We’re getting deep into Lent now, we’re getting closer and closer to those deeply human moments in the life of Jesus—closer to his grief and his pain… and that’s why I chose this passage for today. “In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to those who would save him from death…”. The other lectionary option for today that I was thinking of preaching on is from John 12—in verse 27 Jesus says, “Now my soul is troubled. And what should I say-- Father, save me from this hour? No, it is for this reason that I have come to this hour.”

This is what the author of Hebrews believes proves Jesus’ perfection—this complete submission, completely giving in to the pain that awaits him. And this perfection is, according to the author, what absolves all of us of our own sins and our own faults… it’s what allows us to receive that grace when we falter and when we lose sight of what matters.

Jesus was at once human and scared; and yet he was also divine and willing. What do we do with this contradiction? How do we even start to think about living up to the impossibility of perfection? Do we even try?

Well first, as always, we need a little historical background here. Like last week, with our scripture passage from the Ephesians, I wasn’t super familiar with this minor epistle to the Hebrews. And like last week, this was both not written by Paul, though it was originally attributed to him, and like the letter to the Ephesians was neither a letter or written specifically to the Ephesians, Hebrews is also neither a letter, nor written specifically to Hebrews. It’s more of a sermon, and it’s kind of a strange one at that—the author uses this mysterious character of Melchizedek to prove his points about the divinity and perfection of Jesus. Melchizedek is only mentioned twice in the entirety of the Old Testament, and both times, he’s only there very briefly. The author seems to be using the ambiguity and mystery around this character to prove his point, in a way—his claim (which he explains in great and confusing detail in chapter 7), is that since Melchizedek was this lone high priest who had the duty of blessing Abraham, then still Abram in Genesis, he was, above all other priests—there are also non-Biblical legends about a miraculous birth, there’s no genealogy to speak of, so there’s an assumption he was born divinely— and let me tell you, it certainly sent me down a rabbit hole. But ultimately, Jesus is a high priest in to be revered as Melchizedek was—but because of his sacrifice, he goes beyond, and because of his resurrection, he retains this version of high priesthood forever.

It's a lot. It’s convoluted. And it was written by an early Christian who was preaching to a group of early Christians getting tired of waiting around for the second coming that was promised as imminent, and they were getting tired of being persecuted while they waited. He was trying to convince them to hold strong and keep the faith, to understand that by sacrificing, they were on a path to perfection.

We rational New Englanders may not be entirely convinced by some tenuous connection to a mysterious high priest who appears mostly in legend outside of scripture… but I’m always moved by the humanity of Jesus in the season of Lent. I’m always moved by this eternal contradiction of human and divine, of strength in weakness— and in fact, this is something Hebrews emphasizes just before our reading for today. In chapter 4, verse 15 and chapter 5 verse 2 respectively: “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sin.” Again, a beautiful example of this author’s vision of perfection—human and weak, and yet still without sin; and then, the author speaks of fully mortal high priests, “He is able to deal gently with the ignorant and wayward, since he himself is subject to weakness…”. Someone in power who is striving for perfection will be compassionate towards those who are lost because they will have a deep understanding of what makes a person become wayward and loss themselves, and they will therefore be able to have a deep and real empathy and connection with that person.

This is the convincing part to me. This, if I were one of the discouraged in the pews for this ancient sermon might convince me to stick around—this idea that Jesus was subject to weakness despite his perfect divinity… that Jesus is the ultimate and perfect guide and yet knows every sorrow, every pain, every bit of grief and longing we have ever felt. There’s such a deep solidarity there that is only possible in a savior both divine and deeply human.

But what do we do about this concept of perfection? This is a recurring theme throughout the book of Hebrews. Because this isn’t just about trying to prove Jesus’ perfection—it’s also about how we should strive for perfection ourselves. At the beginning of chapter 6—“Therefore let us go on towards perfection…” Later on, in 7:11, the author talks about how before Jesus perfection wasn’t attainable; in 10:14, “…by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are sanctified…”, in 12:2—that we must “look to Jesus as the pioneer and perfector of our faith…”. And there are even more references to perfection throughout this book. It feels impossible, doesn’t it? To strive towards perfection? As someone who is very far from being a perfectionist, I have no desire to try for perfection. That’s why I like the humanity of Jesus! Don’t make me try for the divine part!

But I wonder if it’s less daunting if we think of the idea of perfection the way the ancient philosopher Philo of Alexandria thought about it. And credit where credit is due here— this is another time where being married to a philosopher comes in handy. Now, even though Philo was a Greek Jew, his thinking influenced Christian theology more than so many other ancient thinkers. He was a contemporary of Paul, and he had quite a bit to say on the concept of perfection.

Philo believed that perfection involved regulating our nature, controlling our emotions in order to perfect our spiritual practice, and he believed that doing this was, indeed, working towards godliness—and yet! At the same time, he believed that the absolute worst sin was that of hubris and lusting to be a god, and so part of this work of perfection was recognizing that we are nothing; and we are especially nothing without the grace of God. So we work towards perfection while recognizing our utter insignificance and powerlessness. Seems like this work for perfection just got even more confusing and impossible.

But it’s this nothingness and this powerlessness that I think we really have to embrace. It’s this, to use the cliché, letting go and letting God, to an extent. Philo believed that “…there are no natural limits to [humankind’s] perfectibility when they accept to submit themselves to the power of God.”[i]

And even though Philo was indeed a Jewish man, I think we can see why this thinking was so influential to Christian thought. Jesus is the epitome of someone who wholly submits himself to the power of God, for the sake of all humankind. Jesus shows us what to aspire to— practicing with all our hearts, the faith that we know, despite how hard the journey is, we are on the right path, and God is leading us to the right place—leading us to create an earth as it is in heaven, the ultimate happy ending.

Because translated from the Greek, that’s also what this idea of perfection is— it means reaching completeness, reaching maturity. And doesn’t that feel like it might actually be possible? Normally, when we think of the concept of perfection, we think of Jesus; we think of something completely unattainable, something that’s impossible for any flawed, fallible human to aspire to. But when we think about in terms of reaching maturity, reaching our full potential, not as an individual, but one body of people reaching the ultimate goal of a just world for all— one body of an entire people working towards perfection for all people, as one. And now, this may not happen tomorrow, it may happen not in our lifetimes, or our grandchildren’s lifetimes, but doesn’t it actually feel like some day, reaching that end goal could actually happen? If we think about striving towards perfection less as trying to be a god, and more like working towards an ultimate goal of creating a world where everyone is safe, where everyone is comfortable, where no one has to worry about how or when they’ll get their next meal, where no one has to worry about indiscriminate bombing, needless war, or violence of any kind, it feels like something we not only can strive for, but we must strive for.

Another thing I really love about Philo is his concept of God—he has a negative concept of God—not negative as in bad, but negative as in, wholly unknowable. Philo perceived God as a blinding light, completely omniscient and omnipotent and gracious, both completely unknown to us, and yet incredibly close to us, all around us all the time. And it is in this unknowable God that our faith must lie. We give our lives to this unknown, because it means letting go of any control, of any sense that we have any power over our own lives. It means we let go of our ego, and when we let go of our ego, it means we can act in service to others, always.

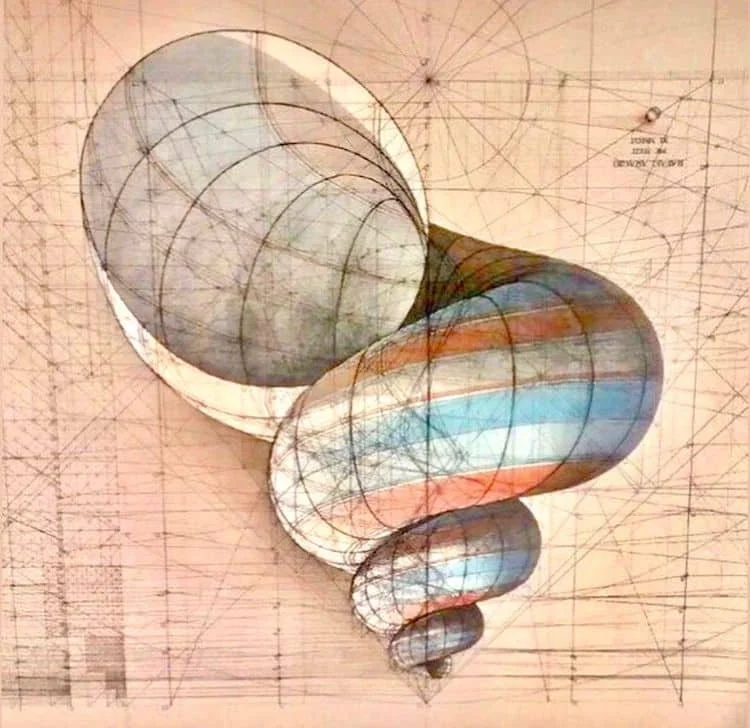

And so maybe it’s in this divine mystery, that we find the meaning of this strange figure of Melchizedek. Maybe it’s the very fact that he’s mysterious and shadowy and unknown that makes him such a perfect springboard for the author of Hebrews. Maybe it’s the fact that we don’t know anything about this strange high priest who is human, and yet, possible has some… divine characteristics. Maybe he represents the divine mystery of God, and then Jesus completes the circle by being born of this divine mystery, by dying of this divine mystery, and then of rising again.

As we move closer and closer to that triumphant day of resurrection, to the culmination of the divine mystery, we have to get through the humanity first. We will hear Jesus’ pleas, his cries. We will feel is disappointment and his grief. We will experience the mysterious fact that Jesus can at once be weak and deeply vulnerable and also be perfect—and that perfection is because he is the end-all-be-all. He closes the circle by giving himself to God and giving himself for everyone on this earth.

And so for the remainder of Lent, let’s think about striving towards perfection—not perfection as some sort of unattainable ideal, but perfection as in working for a completely matured world— a world that is wholly complete, in that not a single person is left wanting. And we’ll do this by being strengthened by the solidarity that we feel with Jesus as we enter Holy Week; and we’ll do it by embracing the mystery. Amen.

[i] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/philo/#VirtPathPerf